the future of living in period historic houses

by fmgarchitects.

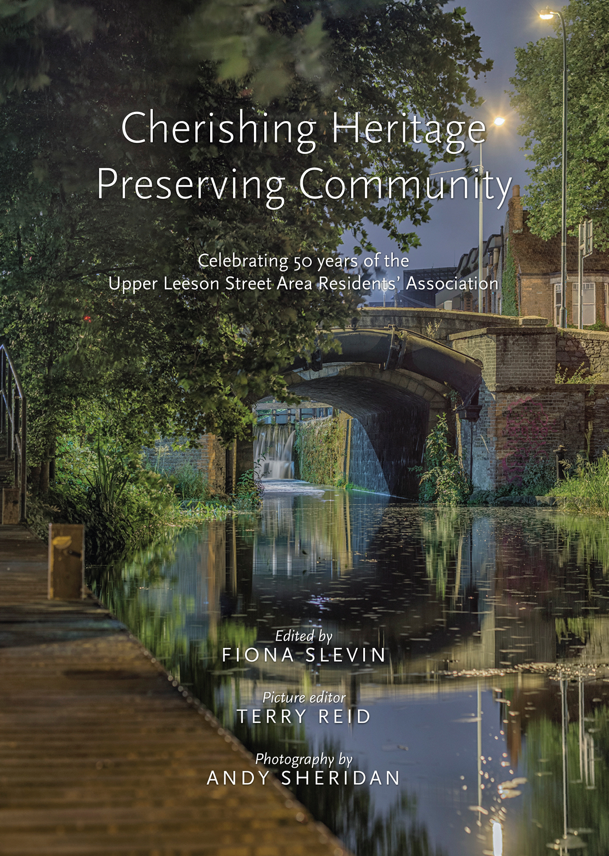

The Upper Leeson Street Area Residents Association (ULSARA) have celebrated their 50th anniversary with the publication of a book of essays which describe the history and character of the area as well as the associations fight against uncontrolled development in the 1960s in the area. We were delighted to contribute to the publication with a chapter on “Living in an old house in the future – What will the next 50 years hold?”. The chapter explores themes including the international image of historic suburbs, future challenges and heating & energy use. The text of the chapter is reproduced below.

The future of living in period houses – what will the next 50 years hold?

People do not generally want to live in a city or urban neighbourhood that is indistinct from other global cities. The specific identity of a city, its sense of character and place stems from its built heritage – places, buildings, whole streets and neighbourhoods of the city that embody the history and past culture of the place and encourage people to consider their place in time.

A global study conducted by IPSOS MRBI in 2013 found the best cities in which to do business were New York, Abu Dhabi, and Hong Kong; the best in which to live were Zurich, Sydney and London; and to visit were Paris, New York and Rome.

In a subsequent survey of two hundred Irish 25-44 year olds taken in the spring of 2015, with Dublin now included as an option, the top-ranked cities in which to work were New York, Dubai and Dublin; it has been three years since this survey and Dublin’s credentials may be now tarnished by the developing housing crisis. The best ranked cities in which to live in were New York, Sydney and Dublin, and the best ranked cities to visit were New York, Paris and Rio de Janeiro.

Interestingly “the knowledge generation” do not see the cities of the future as “futuristic,” for example like Dubai or Hong Kong. They do not necessarily want to live in these cities. The best cities of the future are seen as innovative, safe, young, fun and clean, with great parks. Vancouver, Sydney and San Francisco are cited as the best examples of these.1

The Upper Leeson Street area represents in this respect an ideal city neighbourhood, with fine streets of unique historical character, good parks and proximity to the city centre and business districts.

What is the future of the Upper Leeson Street area for the next fifty years? Lorcan Sirr points out in “Dublin’s Future – New Visions for Ireland’s Capital City” that prediction is pointless but preparation for the future is invaluable. Facing the future and thinking about it in a considered way is a means by which we can direct it to a certain extent and also, more importantly, be ready for it.

The unique character of the area

For most of the 20th century, there was an attitude among elements of the public, construction professionals and city authorities that our period houses and the streetscapes that they framed lacked intrinsic value and symbolised a colonial past; and a large part of the city fabric was lost, accelerated by events such as the 1963 tenement collapses at Bolton Street and Fenian Street.

One could conclude that the worst times for these houses are probably over. Since the late 1980s a more enlightened attitude has developed in relation to the value of our 18th and 19th century built heritage and the unique period of Irish craftsmanship that it represents. Better legislation is in place to protect our historic building stock and the building industry has re-trained and to a large extent remembered the traditional skills and knowledge necessary to look after them.

The significance of the architectural heritage of the Upper Leeson Street area is evidenced by the density of protected structures along its principal streets as well as by the Dartmouth Square architectural conservation area. The area is possibly Dublin’s first suburbia: built outside the canals principally in the 19th century at a safe distance from the threats of the old city but still within walking distance. The deep front garden plots typical of the area facilitated flights of steps to raised entrance level which allowed the basement levels to rise out of the ground, unlike their Georgian predecessors. Dublin house typologies evolved from the straitjacket simplicity of the classical Georgian terrace to a multitude to Victorian styles.

To live in a period home is to live with the aspirations, fashions and culture of earlier centuries. This is not nostalgia: contemporary lives can be facilitated within the well-proportioned rooms whose character and features are animated when winter fires are lit; houses that have no straight lines, and creak and make noises in the middle of the night; houses that exude character but also create a duty of care for their owners. The buildings manifest a physical tangible legacy in a way that is not possible in literature, nor in other art forms.

Future Challenges

The area will face challenges in years to come. The ULSARA residents’ association was originally formed in 1968 to challenge the change of use of residential properties to office use. As average family sizes continue to fall and the demand for smaller residential units increases, the relevance of larger domestic properties may be called into question. As Dublin becomes a global city, can a sense of community be retained in the area, unlike for example areas of central London?

A 2008 Eurobarometer poll noted that only 31% of Irish people would consider moving to a smaller house in the same location compared to 60 per cent of Danish people or 57 per cent of Dutch people.2 One in seven Dubliners lives in a period house. Given the typically large size of the housing stock in the area, the difficulties in adapting them and the shortage of smaller housing units in the area with an ageing population, this will be an ongoing challenge for the community.

The concept of custodianship is often raised in relation to period houses. They have lasted generations, endured wars and recessions, and will outlive their owners. As such we are only minding these buildings for the short period of our lives. In that context and in the relatively recent culture of modernisation, are over-zealous renovations and modernist extensions completely justifiable? Perhaps people could adapt more to these houses, that have survived relatively unchanged for over 150 years, rather than the buildings being unnaturally over-extended? Sometimes a period house can look unhappy when all of its primary functions are decanted out of the main body of the house into the ubiquitous glass extension to the rear garden, a trend that has become established only in the last twenty years. A pattern of individuality from its neighbours develops which ultimately will result in uniformity.

Heating and Energy

One of the largest challenges for the future may be the ability to heat large period homes to improving modern standards. Ireland will struggle to meet its commitments to the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) for developed countries to reduce their CO2 emissions by 80 per cent by 2050 and the EU Climate Energy Package target to reduce emissions to 20 per cent below 1990 levels by 2020.

Housing is Dublin’s biggest consumer of energy, accounting for 35 per cent of the city’s primary energy consumption, comprised mainly of imported fossil fuels. Ireland imports 89 per cent of its energy, making us one of the most energy-dependent countries in the EU and Dublin one of the most energy dependent cities. Codema has worked with Dublin City Council in developing a Sustainable Energy Action Plan which analyses Dublin’s potential to become an energy-smart city by 2030.

This long-term vision shows how, over the next twenty years, the introduction of carbon neutral and low-energy buildings, improvements in information technology and the development of a low-carbon transport system will help Dublin to reduce its carbon emissions by half. Although an action plan is in place, meeting the city’s emissions reductions targets will be challenging. Period houses do not naturally lend themselves to deep energy retrofits as period features and traditional construction make intervention more difficult. Newly built A-rated houses that can be heated at minimal cost have created a new paradigm and yardstick by which period houses will be poorly judged.

Given the difficulties in energy retrofitting period houses, meeting the owners’ comfort requirements often requires a combination of partial retrofit, change in owner behaviour and additional heating where required. As regards heating, Dublin City Council appointed Danish engineering consultants to undertake a feasibility study on the potential for the implementation of a citywide district heating network. 3 The purpose of district heating is to use low-grade heat sources that would otherwise be wasted and the proposed district heating network for Dublin will circulate hot water in an underground, pre-insulated pipe system. A local district heating system that supplies clean renewable energy to period homes across a large area may be something that will have to be implemented in historic areas of Dublin to preserve the cultural value of the building stock while reducing the carbon emissions resulting from their energy requirements. Dublin city has both the size and concentration of large buildings to host a large urban district heating system, although no such model currently exists in Ireland.

Dublin has other climatic and physical features that may offer clues to future solutions. Our coastal mountain setting may offer potential for further wind and hydro-electric projects. Solar radiation levels compare surprisingly well with other European cities offering potential for solar hot water and photovoltaic electrical generation. There are already signs of innovation: the Iveagh Garden hotel has recently opened in Harcourt Street with its energy being provided by turbines powered by the underground River Swan.4

The Upper Leeson Street area is a unique urban neighbourhood within Ireland and within the world. It will face challenges as the world continues to become more urbanised, however its cultural value and unique characteristics will ensure that it will continue to be a desirable place to live.

References

1 Irish Independent – “Can Dublin be a Future City?” April 2, 2015

2 Dublin’s Future – New Visions for Ireland’s Capital City, Lorcan Sirr and others

3 Dublin Sustainable Energy Action Plan 2010-2020

4 Irish Times – First look: New Dublin hotel fully powered by underground river

No comments on ‘the future of living in period historic houses’

Leave a Reply