how to insulate old house walls

by fmgarchitects.

Above: (Left to right) Calcitherm Caclium Silicate board, Gutex wood fibre board, Remmers iQtherm board, Diasen Diathonite

Above: (Left to right) Calcitherm Caclium Silicate board, Gutex wood fibre board, Remmers iQtherm board, Diasen Diathonite

While many of our traditional buildings have been sitting inefficient and unmolested for several hundred years, the development of improved energy standards and thermal comfort levels in modern buildings in recent years has created a new benchmark against which our built heritage is judged. Things were simpler in ways up to forty years ago when new buildings were often (inexcusably) as inefficient as historic buildings!

Traditionally built walls, (ie: solid-leaf brick or stone construction in the Irish context) absorb moisture externally and were intended to be able to dry out on both sides of the wall when conditions improved, unlike for example modern cavity wall or dry-lined construction with a vapour control layer. There is a large body of technical scientific research into this area – this Heritage Council research document would be a key reference for further reading . This article takes an introductory approach of some of the main issues to be aware of.

Applying insulation layers to traditional walls poses several issues: It can be difficult to work around internal historic features such as shutter boxes and cornices and the visual impact of the insulation may be unacceptable. The wall insulation may have reduced benefit if issues such as excessive air infiltration (such as through a suspended timber floor) are not addressed. Nevertheless, the long term viable use of our traditional building stock needs to be maintained without them being perceived as obsolete or excessively costly to inhabit to a reasonable comfort level.

Above: Caclium Silicate board used around a shuttered reveal. The shutter box was dismantled and moved forward into the room

Above: Caclium Silicate board used around a shuttered reveal. The shutter box was dismantled and moved forward into the room

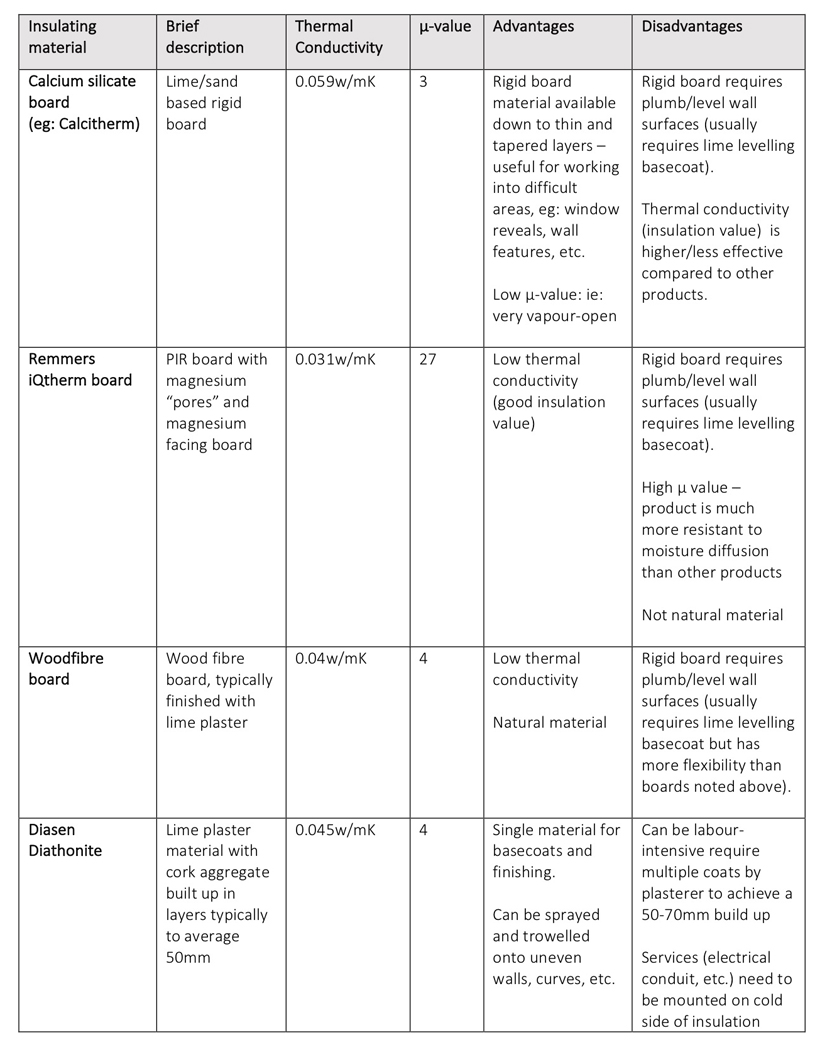

Applying insulation layers internally will make the original wall colder than it was previously and also will reduce the wall’s ability to dry out to the inside. Polyisocyanurate (PIR) board typically used in modern construction, as an example is unsuitable for traditional construction as the foil facing in particular inhibits the ability of the walls to “breathe” and dry out internally. A range of insulation materials that have become common for insulating single leaf walls have become more widely available and used in the last 10-12 years which are summarised in the table below and which we have used on various projects in recently.

From our experience, we see advantages and disadvantages to each system in terms of characteristics and practical application as summarised in the table below. The thermal conductivity of the material (the lower the value, the better the insulation value) varies greatly between the materials and this value seems to trade off with the μ (pronounced “mu”) value which is water vapour diffusion resistance factor – the ability of the wall to dry out with the lower values being more favourable for allowing the wall to “breathe” and dry out without the risk of interstitial condensation and moisture/dampness within the wall.

For example, while the Remmers iQtherm board has the lowest conductivity/best insulation value of the selected products, it has a μ-value which is a multiple of the other products (bear in mind however that the μ-value of the foil facing to typical PIR boards has a value of 100,000+). It is important that these basic characteristics of the products are understood.

Above: iQtherm board applied to a wall (note pores in board) . A thinner section of the board was carried between the joists to avoid a cold bridge at the floor zone

Above: iQtherm board applied to a wall (note pores in board) . A thinner section of the board was carried between the joists to avoid a cold bridge at the floor zone

Many of the suppliers with provide a software-based risk-assessment of the wall construction and the effect of the proposed insulation material in terms of moisture uptake, condensation risk, improvement in U-value, etc. This risk assessment should be done by dynamic simulation software such as Wufi or similar – simple dew-point analysis would not be considered adequate today. If a project is large and complex, the various options and system can be modelled by a consultant who can offer independent advice on the best approach.

Calcium-silicate is a hard, rigid type board. It is based on lime and sand which is highly compatible with old walls. In terms of practical application, the thinner boards are very useful for working into areas where limited depth is available, for example around shutter box and window reveals. The material however has no “give” and walls have to be perfectly level to apply the boards to – usually achieved by a heavy lime plaster basecoat. The material has the best μ-value but the highest conductivity of all the materials listed – in other words, the best at breathing but the least insulating.

Remmers iQtherm is essentially a PIR board (without the foil facing) which accounts for its excellent insulation values being the best of the materials looked at. The breathability of the material depends on magnesium pores embedded within the board which are linked to a magnesium board facing on the inside. The higher μ-value/vapour resistance may be a concern in exposed locations where walls that have a high absorbtion rate (eg: single leaf solid brick walls in exposed locations).

Diasen in an interesting new cork-aggregate insulating lime plaster option which can be built up in plaster layers on uneven or even curved walls and can be finished in a fine or napp/rough finish, the latter often suitable for outbuildings. Used on a project recently, the product was found to be a good product and result but labour intensive requiring 4-5 coats to be built up by a plastering team to an overall thickness that varied from 50-70mm due to the walls being off-level.

Above: Diasen Diathonite insulating plaster applied to a wall. Left – base coats in progress, Right – Napp finish as yet unpainted

Above: Diasen Diathonite insulating plaster applied to a wall. Left – base coats in progress, Right – Napp finish as yet unpainted

In summary, consider your wall characteristics and exposure in relation to the characteristics of the material you are choosing. If the wall is going to get wet, it has to be allowed to be able to dry out. The potentially wetter the wall, the more vapour open the internal thermal lining material that should be chosen. Expectations in terms of high thermal performance should be tempered – modern thermal efficiency standards may not be achievable.

Further reading:

Heritage Council Deep Energy Renovation of Traditional Buildings: Addressing Knowledge Gaps and Skills Training in Ireland (see in particular section 2.5.3.4)

Hi there,

I’m interested in some of the advice in the ‘how to insulate old walls’ description. For some of the named products such as cork lime plaster or indeed the wood fibre, are there any clear advantages/disadvantages to insulating the walls externally rather than the inner face.

Thanks Declan

Hi Declan,

External insulation is a technically good way to insulate as the wall structure is kept warm and the risk of interstitial condensation within the build-up is removed. In conservation terms however the visual impacts can be significant in terms of the impact on external finishes/appearance, window reveal depths, eaves, etc. The building can also look a bit flattened and brand new which can impact on its character. Ive seen it done well but it needs careful though and I would rule it out for any historic building with external features, mouldings, etc.

Hi,

Is it possible to put external insulation on a 100 year old terraced small city house, and not have it look like a box? The house is stone built. Neighbours have used external, but it ruins the look of the house. Would prefer lime plaster, but BER advisor is saying external insulation is the only way to ensure good insulation.

Thanks,

Jayme

Hi Jayne, external wall insulation is technically a great way to insulate old walls as there is no issue with interstitial condensation and the interior wall features are retained. However you’re right, it is having a huge impact on the character of parts of Dublin and elsewhere. It should be possible to achieve a lime plaster finish over a wood fibre board to achieve a “breathing” wall result however it might still have significant visual impact in terms of window reveal depths, eaves, service boxes, etc. It is possible to internally insulate traditional solid walls successfully as per the article however your U-Value/thermal performance would be not as good – typically around 0.45w/m2k as opposed to 0.2w/m2k for modern construction retrofit. This is because the more insulation that it applied, the greater the condensation risk even if a vapour permeable insulation is applied.

Hello,

We are in the process of buying and old 2 story house, over a 100 years old. The outside walls are close to one meter thick built with Natural stone. They were rendered on the outside many years ago with sand & cement, we intend to remove this, rake out the joints and repoint with Lime Mortar to allow the walls to breath and the finished visual look of natural stone. The inside walls are plastered [not sure of the material used yet]. Reading the guide above any advise on what we should use to insulate the house from the inside and achieve a paint finish would be of great help, I think the Diasen Deathonite plaster might run to expensive for us on our budget. Thanks, Kevin.

Hi Kevin, Exposing the stone finishes externally without a render coat increases the exposure of the wall and potential moisture ingress. I would be careful and ask the suppliers of any of the materials in the article to prepare a risk assessment for the thermal lining based on your wall build up, location, exposure, etc. All the approaches noted are quite expensive compared to modern dry lining – I would think around the €120 per m2 depending on preparation, etc.

These were very great suggestions! Looking forward to more.

https://loftandinsulation.co.uk/birmingham